And now for something completely different…

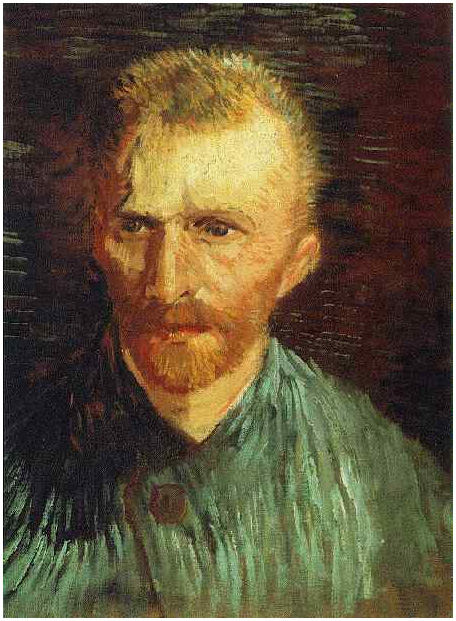

I watched this film/documentary on Van Gogh just a couple of hours ago (related: Netflix instant on blu-ray is a wonderful, wonderful thing). I’ve long been a Van Gogh fan, and I’ve often wondered why, exactly; this documentary, which was brilliant and refreshing (and told with “Van Gogh” himself as narrator–you’ll have to view it to see what I mean), helped me crystallize my thoughts.

It’s the yellow, stupid (meaning, me).

And the heavy brushmarks.

And the wide angles.

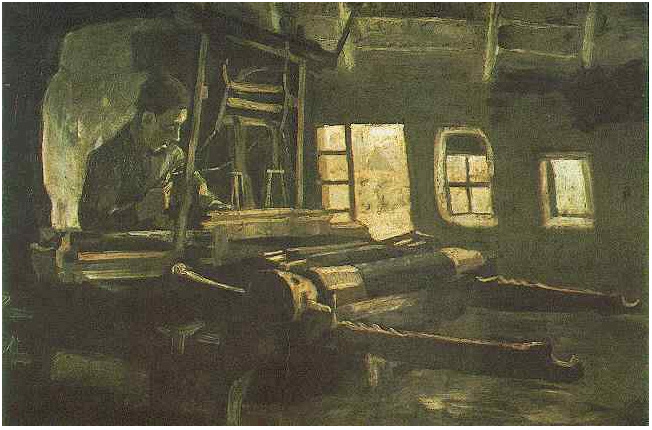

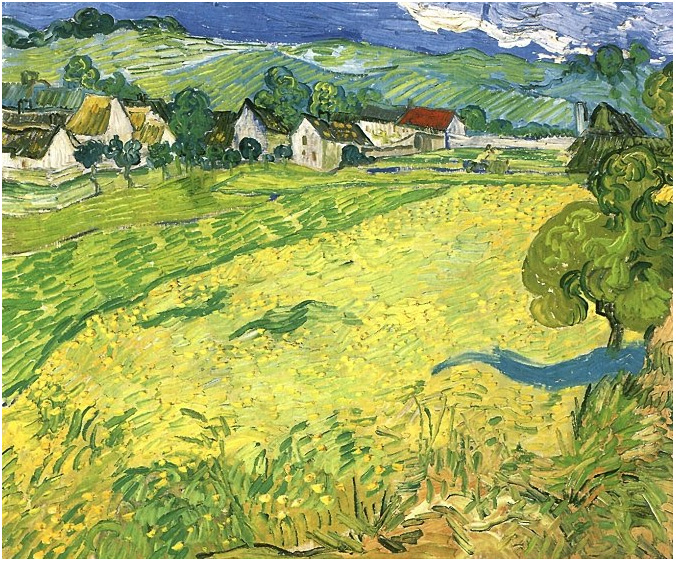

While I still like Van Gogh’s earlier, darker, pre-Arles paintings, it’s the vibrant use of a yellow-blue-green palette that always draws me. Yellow is my mother’s favorite color, and I have many happy associations with it–as does Van Gogh, it appears. While primary-secondary colors in a less-able hand would be childish, and precious, Van Gogh’s colors are instead both comfortable and energizing. That yellow light of Arles, man. I’ve never been there, but I’m damn sure I’d recognize it.

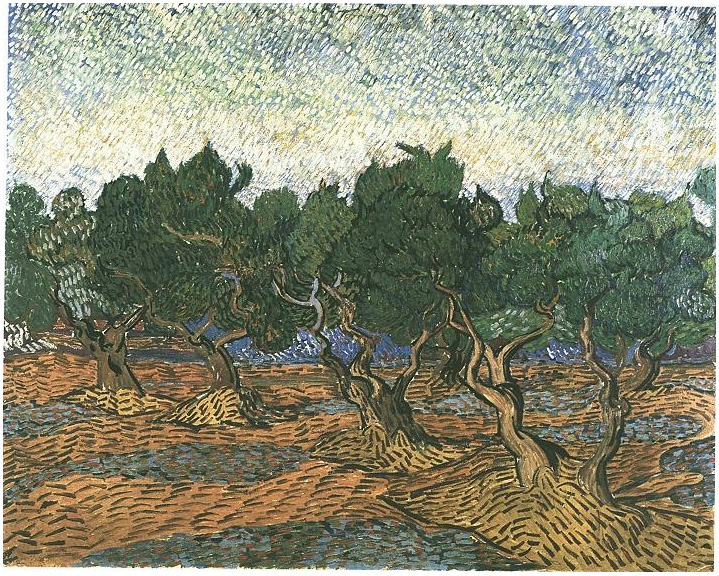

While I’m intrigued by the masters’ blending and realism (and I’m also a fan of J.W. Waterhouse’s mythic paintings), I LOVE LOVE LOVE Van Gogh’s boldness in his brushstrokes. The eye blends; the painter layers and juxtaposes and knifes on. It’s no apologies painting. It’s allowing the paint to have an aria itself, rather than making it stay backstage to the whole image. It’s textual and begs you to touch it (if you’re lucky enough to be by an original).

And, what I never really got at all before watching this documentary today was the viewer’s angle; far distance at midpoint, horizon high, looking down. It’s using a wide-angle lens, which “draws the viewer in” according to the voice over. And it’s true. It’s epic and intimate at the same time. It’s like that great shot in Branaugh’s Hamlet, where his entire “let my thoughts be bloody or be nothing worth” speech is done against a vista of the Norwegian army heading to Poland, in the snow, with a single long shot pulling away.

I only wish that the man behind the paintings, that tormented and driven, prolific soul, could actually be around today to see what a success his work was, after his death. As pointed out in the beginning of the documentary, Vincent only made a pittance during life, selling one, with, what, 900 paintings to his name, but recently his work has drawn the highest resale (82 m) through Christie’s.

Not that money alone is a sign of success, of course. But I wish he could have known how happy, how intrigued, his work would make generations of being around the world when he was alone in his wheat field, or under the olive trees, being led by his muse.